This series examines how pieces of art in London museums speak to or about nationalism by representing or commenting on ‘the nation’. It presents an opportunity for the reader to not only consider the topic in relation to established artists and paintings, but also to plan a visit to the galleries in question in order to experience the pieces of art directly.

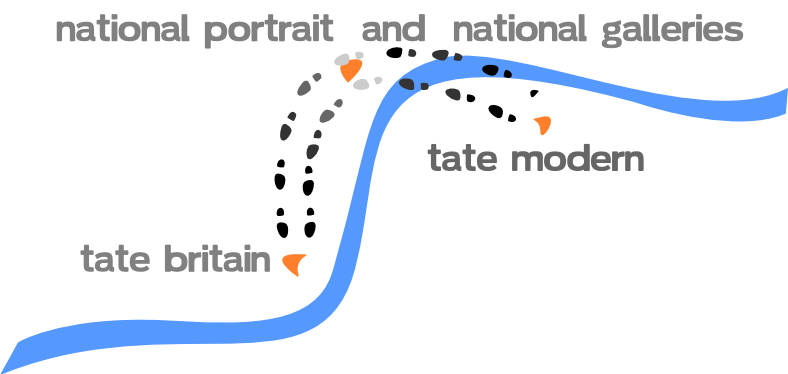

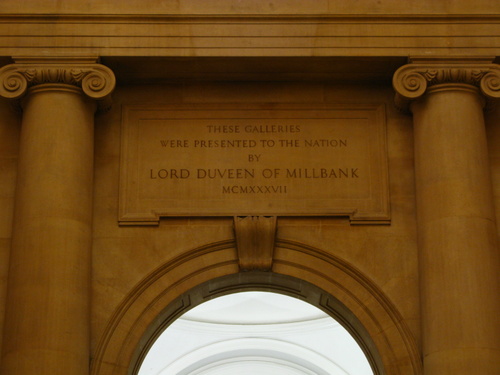

The galleries reviewed were The National Gallery, The National Portrait Gallery, Tate Britain and Tate Modern. Visits to the four couldn’t but lead to a reflection on their different purposes and ethos. Unlike the National Gallery and Tate Modern, references to “the nation” are particularly prominent in Tate Britain and the National Portrait Gallery. We are reminded of this for instance by the engraving (Image 1) when entering Tate Britain “These galleries were presented to the nation”.

to the four couldn’t but lead to a reflection on their different purposes and ethos. Unlike the National Gallery and Tate Modern, references to “the nation” are particularly prominent in Tate Britain and the National Portrait Gallery. We are reminded of this for instance by the engraving (Image 1) when entering Tate Britain “These galleries were presented to the nation”.

In the year 20001, the international collection of the Tate moved further up th e banks of the Thames, closer to the Southbank centre. Tate Britain was formed in the place of the old building out of the collection which remained and has become the home of an avantgarde ‘British modern art’ scene as the venue of the Turner Prize. Tracey Emin, one of its controversial young winners, represents and converses with a sense of ‘Britishness’ as exemplified by the Union Jack in the poster to her most recent exhibition (Image 2). In its self-description Tate Britain elicits firmly the notion of representing and furthering British art:

e banks of the Thames, closer to the Southbank centre. Tate Britain was formed in the place of the old building out of the collection which remained and has become the home of an avantgarde ‘British modern art’ scene as the venue of the Turner Prize. Tracey Emin, one of its controversial young winners, represents and converses with a sense of ‘Britishness’ as exemplified by the Union Jack in the poster to her most recent exhibition (Image 2). In its self-description Tate Britain elicits firmly the notion of representing and furthering British art:

Tate Britain is the world centre for the understanding and enjoyment of British art and works actively to promote interest in British art internationally. 2

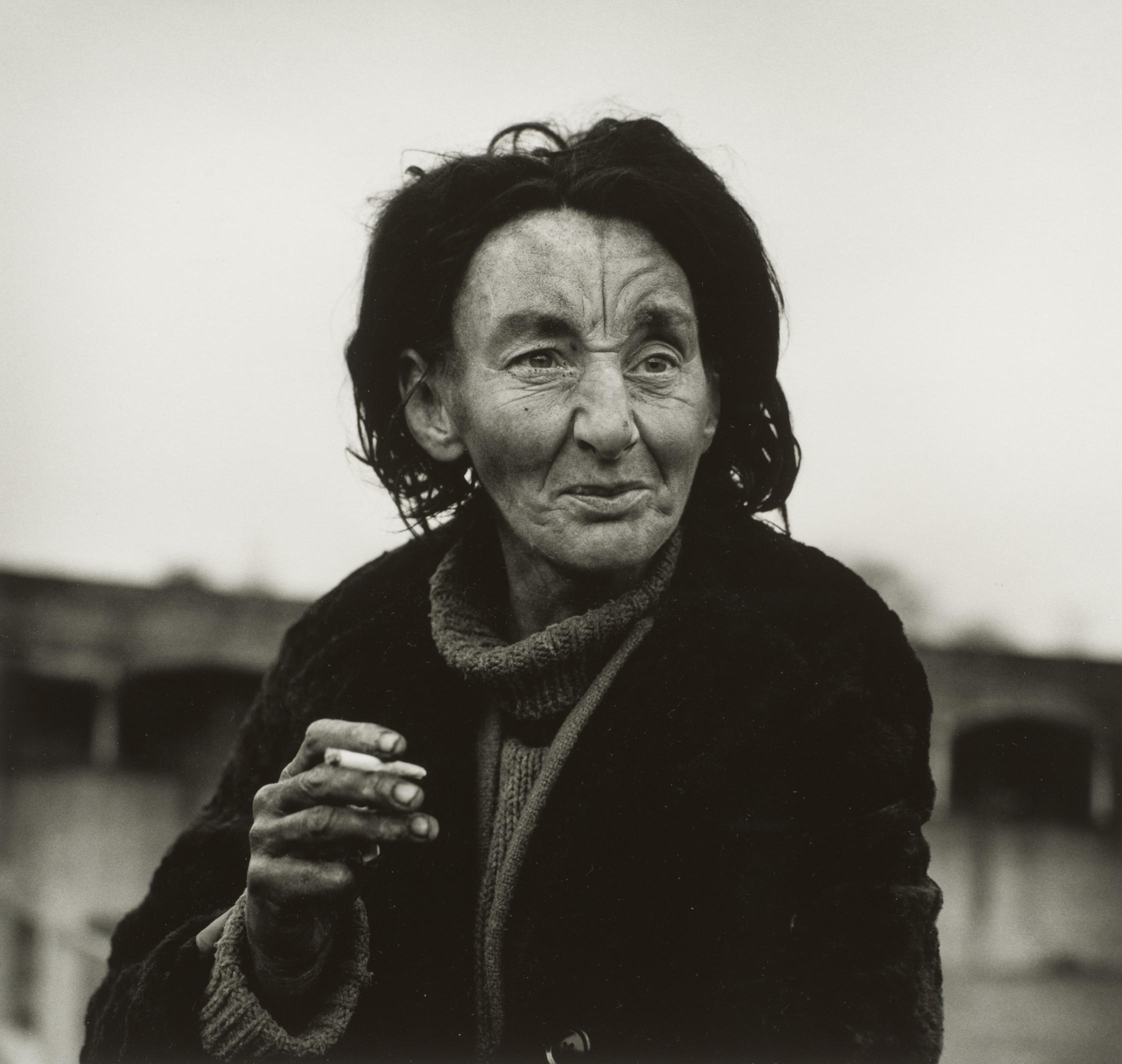

Tate Britain represents “a British nation” when an artist reflects on their place of birth (as an example see Bob and Roberta Smith When Donald Judd Comes to our Place 1997 from Tate Britain; or (Image 4) the Don McCullin photograph of industrial Britain below).

BP British Art Displays - Don McCullin Tate Britain August 15 2011 - March 4 2012 Don McCullin Jean, Whitechapel, London circa 1980 Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper 400 x 380 mm Eric and Louise Franck Collection, London

The National Portrait Gallery, on the other hand, represents the British subject by exhibiting portraits of prominent public figures 3. This can be seen for instance in their ethos when commissioning portraits:

The National Portrait Gallery commissions about six portraits a year as part of its commitment to collecting portraits of those who have made an important contribution to British history and culture. 4

The portraits in the National Portrait Gallery depict people who are perceived to have in some way furthered Britain’s perceived progress over time. Britain is portrayed as being in flux over the ages (see link here) without losing its firm existence. One can journey through decades of transformations and key figures which tell a story of who ‘the British’ are. Thus in Room 18 5 we are told of a significant change for scholars of nationalism: from monarchical power towards Romanticism and Revolution. We see the effects of the French Revolution within British politics.

From there on one can perceive a change of scene. Men in black suits and large scale paintings of scenes in parliament replace the colourful livery of royalty and nobility. Moving downstairs, another change – reformists and parliamentarians give way to celebrity, with Dame Judi Dench, Michael Parkinson and Helen Miren taking key positions next to walls of established actresses and comedians, a dishevelled Russell Brand stares out from a photo, while a bit further down we see the lonely figure of a recent general.

The pieces of art in the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Britain constitute official and authoritative representations of “the British nation”. It is the purpose of the three-part series of essays on “Art and Nationalism in London Museums” to describe some of these representations in more detail.

by Vesselina Ratcheva| 1 BBC News: Artists unveil Tate Britain |

2 Tate Britain: About |

| 3 Kate Middleton Portrait Commissioned Through NPG |

4 Commissioning portraits |

| 5 Room 18: Art, Invention & Thought: The Romantics |

* We would like to express our gratitude to the Tate for allowing us to use certain images from its collection free of charge.

Pingback: Unit Sixteen – Museums and Construction Communal Identities (Nations and Ethnic Groups) | Qualitative Research Methods in Socio-Cultural Anthropology -Tbilisi State University-Manouchehr Shiva

Pingback: Part 1. Narrating the Road to, and Reality of, Multicultural Britain | SEN Journal: Online Exclusives

Pingback: Materiality of Body and Matters of Size, Movement, and Place in Patara Dmanisi | TaaMaaT

Pingback: Body Materiality and Matters of Movement, Size, and Place in Patari Dmanisi | My Blog