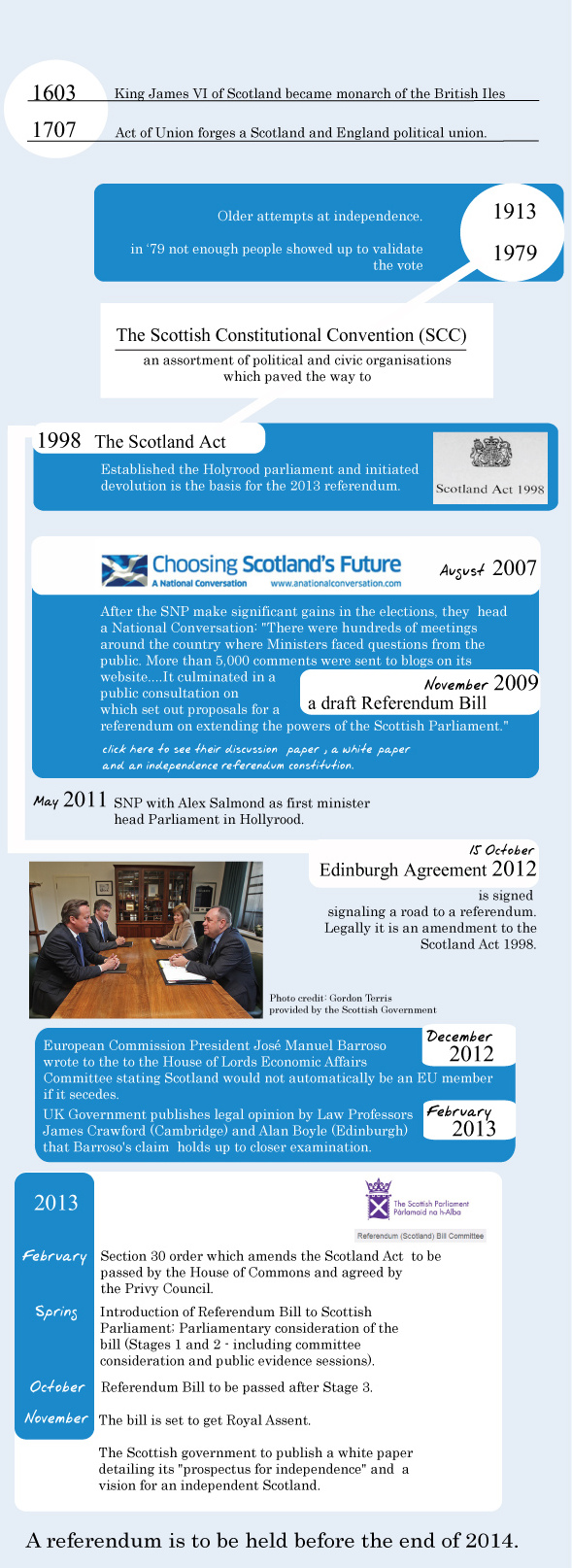

As part of our current series on Scotland and secessionist movements, Professor David McCrone and I met to discuss Scotland’s future in its capital, Edinburgh.  In the first part of that interview, which the SEN blog published last Friday, we discussed the politics of the unfolding process. In this segment, you have the chance to read about Prof. McCrone’s evaluation of the factors likely to influence the vote on Scotland’s independence and his prediction for the Union’s future.

In the first part of that interview, which the SEN blog published last Friday, we discussed the politics of the unfolding process. In this segment, you have the chance to read about Prof. McCrone’s evaluation of the factors likely to influence the vote on Scotland’s independence and his prediction for the Union’s future.

Let us consider the factors which influence people’s voting decisions. In previous works you have denoted that the secondary category which correlates to voting behaviour regarding nationalist agenda is ‘being male’.

That awareness reflects survey work. A lot of the iconography of Scotland is male-centred. Having said that, a few years ago we asked people in England and Scotland which of a long list of 23 social identities they thought they were. We also asked them to prioritize them. We had been told that women and middle class people did not think of themselves as Scottish to the same degree. So, we checked it out. It turns out that women are just as likely to call themselves Scottish as men are, but men are more likely to make political decisions on that basis – such as support for the SNP. This is why the first minister, Alex Salmond, has chosen quite deliberately to play up issues of child-care because his own survey work is indicating there is this slight differential. Being a rather astute politician he has been seizing the opportunity to address this differential. If he was in the room he would he would say: “well of course, I support the principle”. These ‘domestic’ issues have become a salient political opportunity given the changes in the British welfare state of late – such as the bedroom tax[1]. There are also social class issues. Working class people are more likely to support the SNP than middle class people but that doesn’t mean to say that middle class people don’t think of themselves as Scottish. There is a kind of pan-identity across Scotland- “that is who we are” and it’s taken for granted.

Is there any geographic patch-work?

No, there is nothing that you’d notice. People are constantly looking to see “where is it, where is it, what is the factor which ‘explains’ nationalism in Scotland”’. The answer is that there is no simple factor. There is a statistical issue here. Scottish identity is so ubiquitous that you cannot find in statistical terms many variables which are significant in showing the difference.

It’s not that geography doesn’t matter; as a matter of fact it matters so much to so many people that it is just part of the air we breathe. Even things that were built to celebrate British-ness have almost ineffably have been translated into being about Scottish-ness. I tend to give as an example the new town of Edinburgh. It feels very Scottish but actually it was built to celebrate the Union in the 18th century. It is an 18th century new town. What may have been built to epitomize Union can be translated immutably into anther identity. When we find these rather curious transpositions, we start to understand that meaning is not embedded in the object. Consider also Edinburgh castle. It was built as a military barracks. It is still a military barracks but people see it as an icon of Scottish-ness, but of course it wasn’t intended that way. Its main 19th and 20th century history was not such. These are the kinds of transpositions that happen with nationalism. It is not only in Edinburgh that we find these nooks and crannies. Scotland is a variegated country with a strong sense of regional identity and a lot of creative tensions. For example, periodically we have political campaigns asking for Shetland or Orkney – the northern isles – to be independent because “they are not really Scottish”.

So, tell me more about that and how has it arisen?

That has arisen now, it seems to me for political reasons. The Liberal-Democrats seem to be running this campaign. They have seats in the Northern Isles, and few elsewhere. It is as if they have given up on ever being part of the Scottish government again. There has always been that seedbed of being different in the Northern Iles. They reinvented their cultural history as ‘being Viking’. They have great celebrations of burning the great Viking galleons, which is of course a 19th century invention. If you say it’s a fabricated tradition they respond: “oh no no no no!”, but then of course all traditions are fabricated so there is nothing to worry about. This is a political ploy. In fact, all ploys are political, but this is a very obvious one. So you find these things bobbing up as they did in previous referendums, as they did with North Sea oil revenues in the past.

So tell me more about the economic arguments around the referendum. I know these are favoured positions by politicians down south.

Well, it doesn’t wash very well with people. If Scotland became more like Norway in the way of fishing, oil and natural resources it wouldn’t be at all bad. I am not an economist, but if Scotland became independent it’s probably that people’s standard of living would not change radically from what it is now. Scots do not stay in the union because they are bailed out by English tax-payers. It is the other way round. Thatcher was in power for so long because oil revenues allowed her to bail out the British economy. If Scotland had been an independent country in the 1970s when oil was discovered it would be as wealthy as Norway. That money went straight into the British Exchequer to solve the balance of payments problem. People sometimes say I am a nationalist for this line of argument, it’s not a nationalist statement. The Scottish civil service were writing reports indicating that what I have suggested is the case, but these were never published at the time. Annually, the Scottish Government produces what is called the Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland(GERS), which gives some indication of the break-downs but still it is difficult to pin down exactly because of the way Scottish public expenditure is accounted for. It does seem to indicate that Scotland would break even. However it does depend on how you allocate oil revenues. At the moment there are all sorts of boring discussions about the Barnett formula and shares of public expenditure which Scotland gets from Westminster.

My understanding of it is that it frankly does not make a great deal of difference. It is not that Scotland is subsidized hugely by the English taxpayer. Actually, if they showed us the real figures we would be able to work this out, but there is a reluctance to show us the real figures, suggesting that this line of argument is a political, not an economic statement. It does not mean to say that suddenly Scotland would become the land of milk and honey. Another argument that comes up is those who say ‘oil revenues are declining’, yet it doesn’t seem to worry the Norwegians, who are in a similar case. So, in my understanding, the economic argument is not about economics but is about politics.

Scotland has the assets to be a mid-range country in the European Union. Of course, it also has its problems. It was the second country in the world to industrialize along with England and therefore there is a long legacy of de-industrialization. Large parts of Scotland, particularly around Glasgow and Lanarkshire, are still seeking to recover from the legacy of de-industrialisation. Heavy industries like coal-mining, iron-making and steel-making have moved away to China and the far East in a global economy.

The other parallel which has been made is with the Republic of Ireland. The Republic of Ireland however, has a very different kind of economic history from Scotland. With the exception of the North East (around Belfast which is still British) Ireland never had an industrialized economy across the island. It was always a kind of rural economy. It jumped from being a pre-industrial economy to being a post-industrial one. Scotland, whether it liked it or not, was for large parts of its recent history (particularly as part of the Union) an industrialized economy. It was an important part of British imperial enterprise.

Consider also how the Conservatives are currently pulling out Trident[2] as a reason to keep Scotland in the United Kingdom. They have suggested it could help combat North Korea. Well, pretty sure they are afraid of nothing else in Pyongyang than Trident on the Clyde. It costs a huge amount of money. There is of course the vested interest of people working in ship-yards and building bombs, however, you even have members of government in Westminster saying: “Do you need this? Is it a good idea?” The conservatives keep re-iterating that we have to defend ourselves, but as an independent nuclear deterrent it isn’t independent at all. The Americans are the ones likely to make the decision about whether to use nuclear weapons, so it’s all a bit silly, and very costly.

It is not easy to digest as a course of reasoning, especially in Scotland. The Westminster government sends us defence ministers to argue that Scotland would be defenceless, but one could also draw on similarities with Norway where we could ask: “is Norway defenceless?” It has been suggested that an independent Scotland might struggle with expenditure on a defence budget, yet the Scottish tax-payer is already paying for all these ‘fancy war toys’. If the Scots had to list what kind of defence forces they might need, it’s not likely they would include nuclear weapons on the Clyde. So, if nuclear weapons cost 20 billion pounds and Scotland’s share was something like 10%- that’s quite a lot of money. Where could that money be of most use in Scotland? It is not likely to be spent on nuclear weapons on the Clyde.

How do you think mass-concerns about the financial crisis and austerity impact the discourse about Scotland’s independence? Do you think this context, exemplified for example by Royal Bank of Scotland’s mass failure, impacts peoples’ way of thinking about Scottish independence?

First of all, the Royal Bank was never a Scottish bank really except in name. More importantly, the SNP won in 2011. The Banking crisis happened in 2008. That doesn’t seem to fall in line with the argument that nationalism would be waning in times of crisis. It is irrelevant. There is an underlying set of wider economic concerns, but in any crisis there are opportunities as well as concerns.

It depends on whether people judge that things are so uncertain that we’d better just hold onto the status quo for fear of something worse, or there are people who say ‘why not’. There is a perspective which considers that it’s all up in the air now. Yes, the EU is in something of a shambles, so people also think it’s a good argument for ‘getting on with it’. In global history periods of great uncertainty and crisis throw up change in a way that periods of stasis and continuity do not. So maybe there is something in the argument that precisely in the moment of uncertainty you get the opportunities to form new relationships.

If Scotland became an independent country, there would then be a long period of negotiation about what that really meant, who had control of the currency and so on. The division would never be autarchy, North Korea style, but finding a new position perhaps vis-à-vis the United Kingdom. The whole thing has to do with changing relationships, shades of grey or layering new responsibilities. In ten years time, either way, it’s quite likely that Scotland would have much more power than it currently does in the set-up of the United Kingdom, if it is not wholly independent.

Some people say, “you won’t be able to call yourself British”, but I think people are likely to be calling themselves British in the same way that Swedes call themselves Scandinavian. There might be that kind of autonomy of self-definition with the notion of ‘being British’. ‘Being British’ may well be a geographical, cultural and historical descriptor rather than a political constitutional descriptor. People in the United Kingdom seem to agree on British symbols, but it doesn’t mean to say that they buy into ‘being British’; they also make distinctions between English, Scottish and state symbols. This is a rather fascinating set of issues to work out. We have a piece coming out in a journal called ‘Ethnicities’ on symbols of Britain, Scotland and England, which results from our latest research.

It is also very possible that the political-constitutional outcome would be a confederal solution. Of course, if the Scots were to decide to leave the United Kingdom, all bets are off. The Scots, unlike the United Kingdom in wider terms, are less inclined to believe that this is a tight little island in which you can ignore the rest of the world – a fact that large chunks of UKIP and the Conservative party seems to believe. That’s now our way, small countries can’t afford to be like that.

[1] Bedroom tax is a short-reference to current debates about changes to the UK benefits system, whereby people living in properties with an unoccupied (according to terms defined by the legal documents) bedroom are subject to new rules and regulations.

[2] A UK nuclear defence system which is due to be replaced – an issue which is heavily debated.