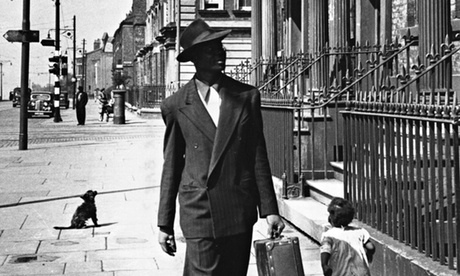

Alex Salmond with Irish Taioseach Enda Kenny and Northern Ireland Deputy First Minister and deputy leader of Sinn Féin Martin McGuinness. Salmond has long regarded the Republic of Ireland as a role model for an independent Scotland.

Irish nationalism today (at any rate the ‘official’ variety) traces the state’s birth to the revolutionary period of 1919-1921, when the Republican movement embodied in the Irish Republican Army and Sinn Féin carried forth a campaign to separate Ireland from Britain. The phrase ‘Sinn Féin’, which has long been synonymous with ‘Irish nationalism’, is often (mis)translated as ‘Ourselves Alone’, but it is true that this expression summed up well enough the essentials of the separatist project for Irish independence that reached an ascendancy between 1918 and 1921. These ‘advanced’ nationalists, in contrast to the moderates of the Home Rule movement, wanted a clean and final break with Britain, and to minimize those ties that would remain necessary. Independence would inevitably mean de-Anglicization as well. (Laffan 1999: 223-224) What is most notable about the Scottish independence campaign, and how immediately different it is to the Sinn Féin example, is how much it wishes to preserve of the existing situation, and how institutions such as the monarchy, the BBC (Scotland’s Future: Your Guide to an Independent Scotland, 2013: 529), the NHS (Ibid, xiv, 12, 47), entitlement to immediate membership of the EU (Ibid, 53), and of course preservation of the existing currency (Ibid, 378-379) are framed as being a part of Scotland’s heritage – one British as well as Scottish – and therefore ‘owed’ to any independent Scotland. The attachment to the preservation of the role of the (British) monarch – Queen Elizabeth – as the Scottish head of state is particularly notable (Ibid, 562). At least as far as ‘official’ Scottish nationalism is concerned, this is hardly a matter of discussion. Objections made by pro-Union campaigners to preserve the pound sterling as Scotland’s currency – through nothing less than a currency union between any independent Scotland and what remains of the UK – have been met with accusations of ‘fear-mongering’ from the Scottish National Party, not the kind of reticence that an outside observer might expect on the whole issue. Across the Irish Sea, however, the dependence of the Irish economy on Britain for several decades after independence was at best a source of quiet embarrassment for mainstream Irish nationalists, and proof of the ‘failure’ of the independence project for the more ‘advanced’ ones. (Ferriter 2005: 463)

In Ireland, by contrast, the British Government’s insistence on the preservation of certain ties between any independent Ireland and Britain (and the Empire), including the absolute demand that any independent Irish state have the British monarch as its head, led directly to a civil war which still has a (faded) legacy in Irish politics. (Laffan 1999: 351) Whereas ‘Old’ Sinn Féin elevated the presumed conflict between Irish and English cultures and nationalities to the level of a clash of civilisations, contemporary Scottish nationalism is distinguished by the absence of such rhetoric. The problem with ‘England’, for these nationalists (or at least their public face) is the unfair advantage it gets over Scotland under the status quo, not with ‘the English’ as a people. SNP campaigners do not use the phrase ‘the English’ as a rhetorical weapon. Indeed, and strikingly, they do not use the word ‘nationalism’ to refer to the Scottish independence project. Where ‘Old’ Sinn Féin envisaged independent Ireland having an autarkic or at least self-sufficient economy, Scotland’s Future elevates the necessity of economic co-operation between any independent Scotland and ‘the rest of the UK’ into a virtue. Where Sinn Féin were/are determined that independent Ireland should have neutrality – to keep out of British wars – independent Scotland will, according to ‘Yes’ campaign claims, apply immediately for NATO membership – so long as the nuclear submarines are removed, of course (Scotland’s Future, 14). Where many separatist Irish nationalists were determined that Ireland should to a certain degree cultivate a position of isolation for the sake of cultural preservation, Scottish nationalism, both in principle and in politics appears as emphatically pro-Europe and pro-EU. (Ichijo 2004)

The SNP’s ‘White Paper’ for Scottish Independence

Beyond a desire to separate from the UK – and even on this the SNP are keen to emphasise the extent to which life will go on much as it does now – there seems in fact little in common between the languages of nationalism in Scotland and Ireland now, and then. That is in itself, perhaps, the point: in the 1920s, all across Europe, rhetoric about the ‘essential’ and immutable ‘character’ of nations and the inevitable conflict of different nations, and the ‘naturalness’ of each nation having its own state, was much more willingly accepted than now, at least in this corner of Europe. The ‘Yes’ campaign, instead of focusing on identity and how to define Scottishness (in contrast to Englishness) and ‘the Scottish people’, deals with ‘the people of Scotland’ and how they could be best served by government. And perhaps the most profound difference of all: if Scotland votes ‘Yes’, the transition will be gradual, peaceful, civil, and democratic. There will be no violence, no paramilitaries, no Scottish Partition, it will be up to the members of the Scottish Parliament alone to decide over matters in any newly-independent Scotland. Yet it should not be forgotten either that Scottish nationalists of the inter-war period did not fail to construct an ‘Other’ for their nation, particularly the Catholic community, and specifically the large Irish Catholic community in Scotland (Ichijo 2004: 129-130). Here there is a parallel, however much its importance in the two contexts differs.

There was once a fashion for observers and students of nationalism to understand the nature of different nationalisms on the basis of how ‘Western’ or ‘Eastern’ they were (which retains some currency in the notion of the ‘civic’-‘ethnic’ distinction). Yet Scotland and Ireland are too close together for that. But while contemporary Scottish nationalism is avowedly ‘civic’ in character, the Irish nationalism that helped make the break-up of the Union of 1800 a reality was a strongly ‘ethnic’ one. (Kee 2000: 426-438) It is the historical contexts of how senses of Scottishness and Irishness developed that matters, not least one important difference: while advocates of Scottish independence could (and do) present it as the restoration of sovereignty lost when Scotland ceased to be a separate kingdom in 1714 (however much that sovereignty may have become curtailed), and at least partially preserved through certain institutions that survived the Union (such as Scots law), this was always a significantly harder claim for Irish nationalists to make. In the absence of relatively uncomplicated institutional and constitutional precedents for Irish independence, Irish nationalists had to stake their positions on the grounds of culture, ethnicity, and sometimes religion, as well. (Townshend 2013: 55-56) If Britishness can be regarded, as Linda Colley argues in Acts of Union and Disunion, as ‘an older form of Scottish national consciousness’, this was always with significant more difficulty the case in Ireland. In the event of independence, however, Scottish nationalists may find this claim to the restoration of sovereignty and re-joining the community of nations tested, with respect to their position vis-à-vis the EU, just as Irish nationalist claims to ‘re-enter’ the community of nations during the Wilsonian moment did not survive the hard realities of British imperial demands. How Scottish nationalists might deal with this problem is, however, speculative.

Diarmaid Ferriter, The Transformation of Ireland, 1900-2000 (London, Profile, 2005)

Atsuko Ichijo, Scottish Nationalism and the Idea of Europe: Concepts of Europe and the Nation (London, Routledge, 2004)

Michael Laffan, The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Fein Party, 1916-1923 (Oxford, Clarendon, 1999)

Scotland’s Future: Your Guide to an Independent Scotland (Edinburgh, The Scottish Government, 2013)

Charles Townshend, The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence, 1918-1923 (London, Allen Lane, 2013)