Guest Contributors

Daphne Halikiopoulou – University Of Reading, Michael Jennewein – Friedrich-ebert-stiftung, Tim Vlandas – University Of Oxford

In almost all European countries, right-wing populist parties (RWPPs) have increased their electoral success at the expense of the mainstream right and left, in both national and European Parliament elections. The rise of Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National is a prominent example. Elsewhere in Europe, for example, Hungary and Poland, right-wing populists are even more entrenched, leading governments and exercising a firm grasp over their countries beyond the immediate political arena. In countries such as Austria, Slovenia and Italy, RWPPs governed until recently.

In almost every country, these parties have managed to influence the policy agendas permeating mainstream ground moving conservatives and progressives alike to the right on salient issues – especially regarding immigration. Even Putin’s war against Ukraine, which some thought would damage European right-wing populists who have cozied up to Russia’s leader in the past, has not significantly altered this trajectory.

A closer look, however, illustrates that this phenomenon is not linear. Right-wing populists have been voted out of office in Austria, Italy and Slovenia, stumbling over corruption scandals and suffering internal divisions. Others, such as the AfD in Germany have seen their support decline. Why are some RWPPs more successful than others? And what role do populism and nationalism play in their success? We address these questions in our recently published FES report on right-wing populism in 17 European countries. In sum, we contest the view that the rise of right-wing populism may be best understood as a ‘cultural backlash’, and argue instead that the role of nationalism is in the supply.

Specifically, we examine three levels of analysis – what we label the Three Ps: People, Parties, Policies.

At the people level the question is whether it is cultural and/or economic grievances that drive RWPP success and, crucially, how these grievances are distributed among the electorate – both the RWPP electorate and in comparison, to the centre-left and entire electorates.

At the party level, we focus on the strategies RWPPs adopt to capitalise on their core and peripheral electorates and how they employ nationalism, populism and welfarism in their narratives and programmatic agendas.

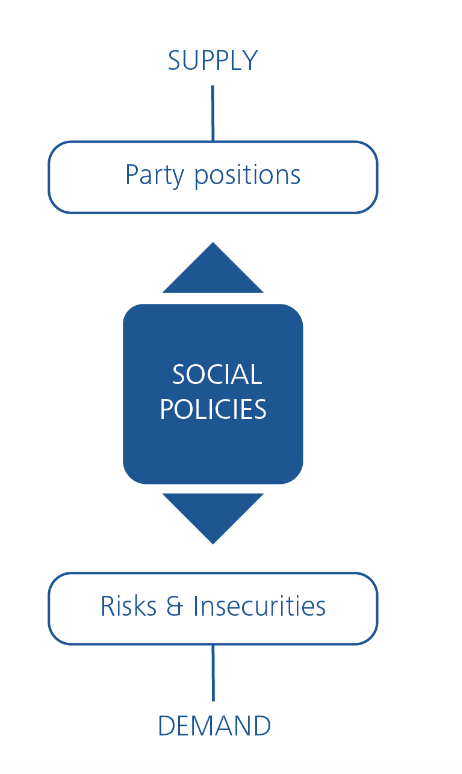

At the policy level we show that social policies matter as they have the potential to mitigate the economic risks driving different social groups within the electorate to support RWPPs.

Three levels of analysis: People, Party and Policy

Our analysis shows the following. First, at the people level, the assumption that immigration is by default a cultural issue is at best problematic. Indeed, both cultural and economic concerns over immigration increase the likelihood of voting for a RWPP. While cultural concerns are often a stronger predictor of RWPP voting behaviour, this does not automatically mean that they matter more for RWPP success in substantive terms because people with economic concerns are often a numerically larger group.

The main issue to pay attention to here is size. The distinction between core and peripheral voter groups underscores this point. Voters primarily concerned with the cultural impact of immigration are core RWPP voters. Although they might be highly likely to vote RWPP, they also tend to be a numerically small group. By contrast, voters that are primarily concerned with the economic impact of immigration are peripheral voters. They are also likely to vote for RWPP, but in addition they are a numerically larger group. Since the interests and preferences of these two groups can differ, successful RWPPs tend to be those that are able to attract both groups. What determines RWPP success is therefore the ability to mobilise a coalition of interests between core and peripheral voters.Second, at the party level, our starting point is that taking populism as an analytical framework is not useful in order to understand RWPPs. For one, this would require bundling both right and left-wing populist parties which we consider analytically distinct as they represent different types of challenges facing democratic institutions. As posited above, it would also not explain the variation within RWPP success as arguably all of them are populist to a great extent. While not denying that populism is one of the main descriptors of the RWPP family, we argue it does not follow that it is an explanatory factor for its success.

Instead, we believe it is much more informative to sift out differences within RWPPs looking at their nationalism as a mobilisation tool that has facilitated RWPP success.

We find that there are regional patterns of types of nationalism in combination with a welfare chauvinist social policy agenda. In Western Europe, RWPPs employ a civic nationalist normalisation strategy that allows them to offer nationalist solutions to all types of insecurities that drive voting behaviour. These parties present culture as a value issue and justifies exclusion on ideological grounds such as laïcité in the French case. Their social policy agenda is – in contrast to the ‘winning formula’ of the 90s – not one of neoliberalism embracing the free market but welfare expansion for the ingroup.

This combination is especially successful in attracting the coalition of voters outlined above of both culturalist and materialist voter groups. RWPPs have been successful at reaching their periphery by capturing of economic insecure social groups who have previously experienced welfare entrenchment at the hands of mainstream parties in power. Eastern European RWPPs, on the other hand, remain largely ethnic nationalist, focusing on ascriptive criteria of national belonging and mobilising voters on socially conservative positions and a rejection of minority rights. While many Eastern European RWPPs propose free market agendas, at the same time they also embrace welfare chauvinism in certain areas such as family policy, acquiring ownership of social issues for their ingroup.

Third, at the policy level, our analysis illustrates that welfare state policies moderate a range of economic risks individuals face. This reduces the likelihood of supporting RWPPs among insecure individuals – for example, the unemployed, pensioners, low-income workers and employees on temporary contracts. Our key point here is that political actors have agency and can shape policy and political outcomes: to understand why some individuals vote for RWPPs, we should not only focus on their risk-driven grievances, but also on policies that may moderate these risks. This suggests that RWPPs success is not a given trajectory. The policies (not) in place do affect the ability of RWPP to capitalise on growing economic insecurities if those do not materials in the first place or are addressed accordingly when they do.

How do these insights apply to the recent French presidential election? Right-wing populist contenders Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour together received 30% of the vote in the first round. Some observers who initially argued that Zemmour might take over Le Pen because he presented himself as the true authentic far right leader who is not afraid of controversy were proven wrong. Le Pen successfully presented herself as a moderate stateswoman capable of tackling numerous crises on the domestic and foreign fronts. It was precisely her focus on economic concerns that allowed her to appeal beyond her core voter base. The inflation crisis which followed several decades of low inflation, and the pandemic aftermath put pressure on an increasing number of vulnerable social groups, allowing Le Pen to appeal to a much larger electoral group facing those concerns. These growing economic problems occurred against the backdrop of longstanding issues facing the French labour market since the economic crisis, liberalising reforms and activation.

At the same time, having Macron with his elitist image and some past record of welfare retrenchment as the opposing candidate helped her narrative as a contender for the middle and lower classes significantly. One could argue that Zemmour’s presence in the race as a hardliner on cultural issues made Le Pen appear even more moderate despite sharing many similar views on this front.

A new RWPP winning coalition?

This suggests that RWPPs pose the most significant threats of winning elections and gaining power when they manage to mobilise a coalition of voters with cultural and economic concerns. As the second group is much larger numerically, responses to the right-wing populist success must also focus on economic questions including rising inequality, labour market insecurity and people’s hardships when facing economic shocks. It is only then that chauvinist RWPP narratives that blame immigrants and minorities are able to find traction among a disenfranchised and economically and socially vulnerable electorate. Governments must also find ways to counter the political polarisation following the pandemic and explore policy innovations such as a Universal Basic Income and Social Investments to address people’s economic concerns and aspirations.