As part of our current focus on sport, SEN Journal: Online Exclusives is delighted to present an exclusive commentary on nationalism and the olympics by Steven J. Mock.

They were a strange sight in the parade of athletes during the Opening Ceremonies of the 2012 London Olympics, stuck between Iceland and India: the “Independent Olympic Athletes”. And I was reminded of Ernest Gellner’s observation that having a nation in the modern world is akin to having a nose and two ears; sure, it’s possible one might lack one of these things, but unnatural, the result of an extraordinary tragedy. These three athletes (apparently from the recently dissolved Netherlands Antilles) compensated for their disability by making the most boisterous entrance they could, dancing their way into the stadium then pantomiming their events throughout the procession. Making light of their absurd condition, they were transformed from piteous to heroic objects: Oscar Pistorius had overcome his lack of legs to become an Olympian; these people had overcome their lack of a nation.

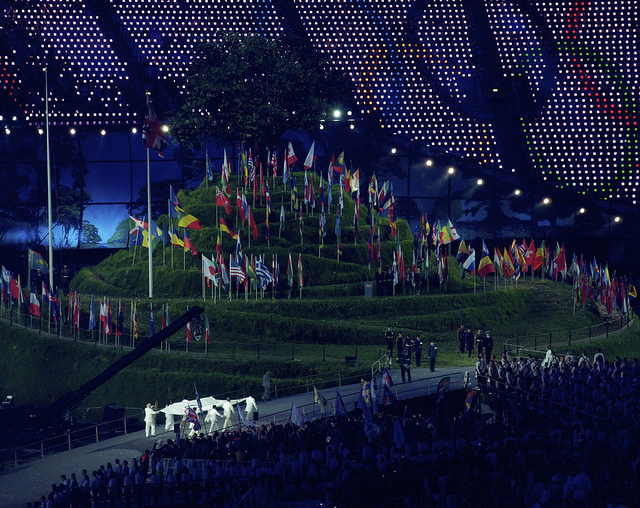

Sport highlights, in many ways, the ambiguous position that the nation continues to hold in our post-modern globalizing world. It is the condition everyone seeks to transcend, yet the inescapable language we must still use to achieve this transcendence. Sport depends on the exertions of the extraordinary individual, or the close collaboration of the team, not any wider imagined community. It sublimates the passions that might otherwise be released on identity conflict into the safe confines of non-violent, rule-based competition. And the Olympics, in particular, are heralded as an occasion when all nations must put aside what divides them and celebrate common humanity in a spirit of peaceful sportsmanship.

But just as international institutions like the EU and UN aim to transcend the anarchy of international relations through the generation of an emergent regional or global community, yet one must first be a nation in order to participate; so too can one participate in the nation-transcending event of the Olympics only as part of a nation – a team that a national institution has organised and sponsored, under a flag, with an anthem, and a dedicated community of supporters whose pride is tied to the athletes’ success. Just as an international corporation might have a budget larger than all but the largest of nation-states, and yet must operate within the confines of territory and communicate according to a particular culture; so too can sports teams engender far greater emotional commitment and catharsis than more explicitly nationalistic symbols and rituals, and yet such teams and the emotions they generate are inexorably tied to signifiers of locality, community, nationality and culture.

This ambiguity was as much evident in what wasn’t in the Opening Ceremonies as what was. National politics aside, the case for a moment of silence commemorating the Israeli athletes murdered forty years ago at the 1972 Olympics in Munich could not have been clearer. Whatever one might think about Israel or the conflict in which it was and remains embroiled, here were eleven people killed as Olympians, wholly innocent victims of brutal violence in a place where violent conflict had no business intruding. Surely it was appropriate for the IOC to articulate such a message. And yet, one cannot take national politics aside, as these were not people without nations. And when their nation is taken into account, commemorating them becomes a political act. Not commemorating them becomes a political act. There is no refuge, even in international sport, from the hegemonic language of nationhood.

Steven J. Mock, Balsillie School of International Affairs, smock@balsillieschool.ca

Dr Mock recently published an article in Vol 10, Issue 1 of SEN on the topic of nation and emotion in television coverage of the 2010 winter olympics. We will be featuring a preview of this piece, as part of our focus on nationalism and sport, next week. Stay tuned.