SEN Journal: Online Exclusives is excited to bring you the latest feature for our current theme on nationalism, ethnicity and art. We are pleased to present this exclusive interview with Inga Fraser, Assistant Curator of the Contemporary and Later 20th Century Collections at the National Portrait Gallery, in London, UK.

Founded in 1856, the National Portrait Gallery seeks ‘to promote through the medium of portraits the appreciation and understanding of the men and women who have made and are making British history and culture, and to promote the appreciation and understanding of portraiture in all media’ [1]. Over the last thirty years the Gallery has commissioned some 160 portrait paintings, sculptures, drawings and mixed media works, as well as many photographs, which form the backbone of the Contemporary Collection.

Karen Seegobin interviewed Inga Fraser on the role of nationalism in the process of commissioning portraits for the National Portrait Gallery.

Thank you so much for taking the time for this interview. Perhaps we can start with a brief introduction of your role in the process of commissioning portraits at the National Portrait Gallery.

Zaha Hadid by Michael Craig Martin, 2008 © National Portrait Gallery, London; commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery with the support of J.P. Morgan through the Fund for New Commissions

I work with the Director, Sandy Nairne, and the Contemporary Curator, Sarah Howgate, on the Gallery’s commissions programme. In the initial stages, my colleagues and I look at prospective subjects by professional groupings and ideas for portrait subjects submitted by artists, trustees, staff, visitors and the wider public, paying attention to those already represented in the collection to avoid duplication. I prepare biographical information to take to the Trustees meetings, in which potential subjects are discussed and a selection is made. Following the decision, we write to the subjects and set up an initial meeting to discuss the process and prospective artists. Finding an artist for a commission is a collaborative process with the sitter and, although the Gallery makes the final decision about the artist, it is in close consultation with the sitter. At this point, my role is to encourage the process towards completion. Though we provide support and guidance where necessary – for instance relating to materials or facilitating sittings – the process is essentially left in the hands of the sitter and artist. Upon completion I will prepare notes on the work to take to the Trustees meeting where the portrait will be formally considered for acceptance into the permanent collection.

Can you tell us about the decision-making process in choosing a subject, such as Dame Vivienne Westwood or Neil MacGregor, of whom represents Britain or ‘Britishness’?

The aim is not to ‘represent’ Britain or ‘Britishness’ per se, which would certainly be a difficult task for any subject. The objective of the Gallery is rather to celebrate men and women of achievement, who have shaped British history, who are making British society and culture what it is today. This includes those who are based overseas. The National Portrait Gallery collection is, by necessity, selective rather than comprehensive, and the commissioning programme is intended to supplement, rather than replace, other forms of collecting, enabling us to represent subjects of whom good portraits may not otherwise be available. The Gallery considers potential sitters from a variety of backgrounds, and decisions on subjects for commissions are made annually by the Trustees as a body with a view to selecting about half a dozen individuals from a longer list. Our aim is to represent the breadth and diversity of contemporary British society in our Collection.

Is the conception of “British” or “Britishness” singular among the selection committee, or are there different notions at play? If so, can you tell us about how they have stayed constant or have changed over the years?

‘Britishness’ is open to interpretation. You could argue, for instance, that some of the people in the Collection such as Madonna, Nelson Mandela and Tim Berners Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, do not tally with the stated aim of the Gallery. Although they are based overseas, they are nevertheless international figures who have contributed to British culture in a meaningful way. As laid down at the Trustees’ second meeting on 16 February, 1857, it is the rule ‘to look to the celebrity of the person represented,’ in the first place when considering whether a sitter is eligible for the Collection. Notions of ‘Britishness’ are inevitably time-bound and change with each generation. It is the Gallery’s aim to reflect these changes.

Would you describe the selection process as tilting towards choosing people who represent Britain’s history or future, or do you try to get a mix of both?

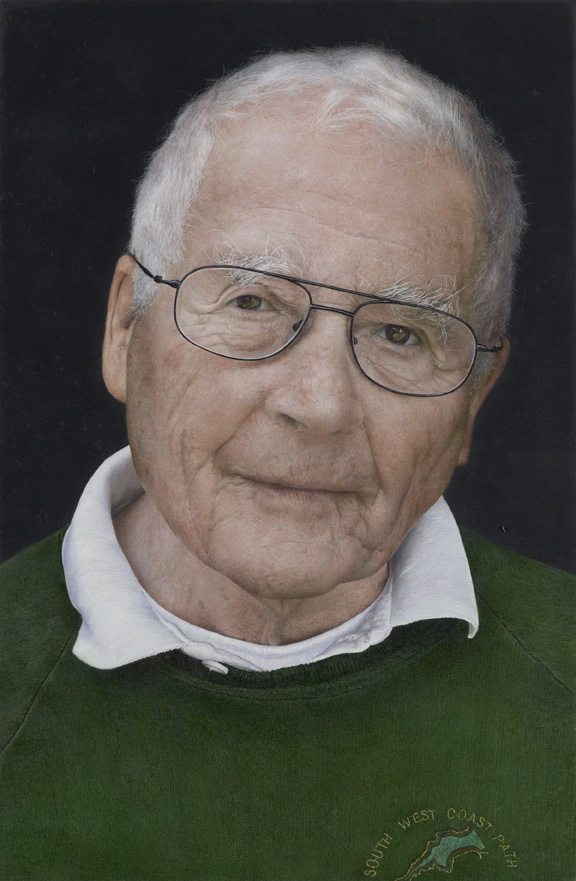

The Gallery is as much about British identity and society today as it is about British history and biography. I find enormous strength in the fact that the Contemporary Collection presents a continuity of forms, whilst at the same time welcoming new approaches and a broad range of subjects. As the Gallery’s current display, Contemporary Portraitsshows, the ways in which artists interpret portraiture today is sometimes remarkably consistent with historical tradition. In works such as Julian Opie’s portrait of the inventor Sir James Dyson we find a desire to depict the heroic, translated into a 21st century aesthetic. In Michael Gaskell’s recently completed portrait of James Lovelock, we see the age-old impulse to record a more personal image, executed on an intimate scale, used nevertheless to show a sitter whose achievements in the field of environmental science are inherently modern. In the selection process, the Gallery’s aim is both to choose subjects whose contribution to British culture is widely acknowledged, but also to celebrate figures whose reputation may not be so established but whose achievements at a particular moment make it an appropriate time to begin a commission.

Do the chosen artists go through a similar commissioning process?

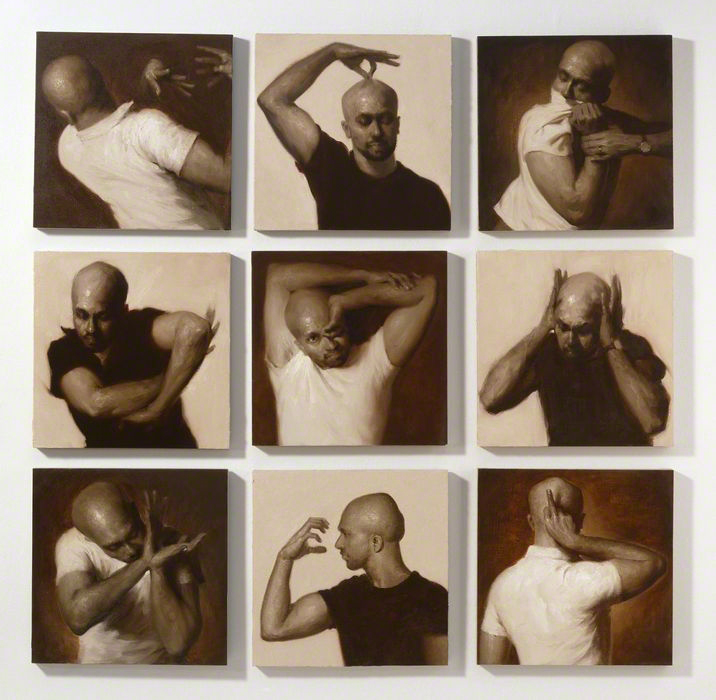

The artists are carefully matched to the sitter and yes there is a selection process. The choice of artist for a commission is naturally very important. If there is a prior connection with the sitter this can be helpful. Current practice is to meet with the prospective sitter to discuss the choice of artist, perhaps stimulated by an exploration of portraits on display at the Gallery. The Gallery has consistently been willing to take risks, whether by encouraging young artists or by approaching more established artists who may not have undertaken a portrait commission previously. By commissioning portraits in a range of media and from a variety of good artists, the Gallery hopes to encourage portraiture and to keep the representation of the human figure very much alive.

Akram Khan by Darvish Fakhr, 2008 © National Portrait Gallery, London; commissioned with help from the Jerwood Charitable Foundation through the Jerwood Portrait Commission, 2008

Have you noticed a change in the recent era in who the public considers an important person? I’m thinking of the connection between the National Portrait Gallery’s recent exhibition, The First Actresses: Nell Gwyn to Sarah Siddons, and the rise of the celebrity in British society.

When the Gallery was set up there were far more men than women represented in the Collection and many of the sitters were statesmen, soldiers, clerics and other such establishment figures, as well as people in the arts and sciences and social reformers. But a sitter had to be dead for ten years before being permitted to enter the Collections (with the exception of the reigning monarch). Sir Roy Strong changed this rule 1969 and since then, living sitters have been admitted into the collection. Following that decision, there have been a greater number of subjects included in the collection drawn, for instance, from the fields of fashion, sport and contemporary music. As the First Actresses exhibition showed, British culture has in the past found a place for men and women of achievement who have risen to fame from a variety of backgrounds, but perhaps now that place is more prominent. Who the public considers to be an important person will inevitably be subject to the ebb and flow of popular opinion. But, essentially the desire to document, to commemorate and to reflect upon prominent figures in our society remains a constant.

Last question: it has recently been reported that Kate Middleton, the Duchess of Cambridge, will soon sit for a portrait. What responsibility does the Gallery feel in portraying her to the nation and world?

The Gallery will take great care, as it does with all its portraits, to find a fitting artist for the Duchess, and we are delighted that she has agreed to sit for a Gallery commission.

Again, thank you for taking the time to speak with SEN Journal: Online Exclusives about how art intersects with the nation. The topic generates much discussion and we appreciate the insights from the National Portrait Gallery.

Thank you.

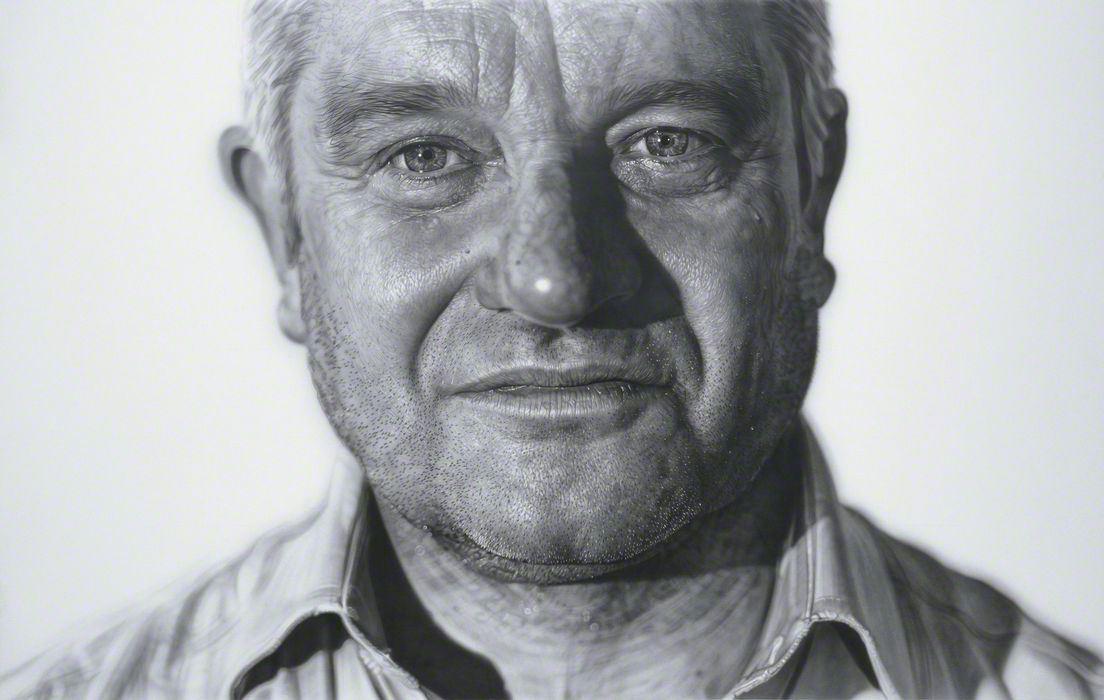

Sir Paul Nurse by Jason Brookes, 2008 © National Portrait Gallery, London; commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery with the support of J.P. Morgan through the Fund for New Commissions

[1] npg.org.uk

For more information on visiting the National Portrait Gallery please visit their website.

*We would like to thank the National Portrait Gallery for their assistance as well as for providing us with the featured images free of charge.