By Dr. Karen Shelby

Since the creation of the Belgian state in 1831, some members of the Flemish community have maintained citizenship as Flemings rather than as Belgians and have located their desire for independence from Belgium directly within the concept of a long-suffering and thus martyred history under Belgian (i.e. French-speaking) rule. This ideology is clearly articulated in two sets of stained glass windows located in the unusual and controversial IJzertoren Memorial Museum in Diskmuide, Belgium. Conceived as a memorial to the Flemish men who died at the Belgian front during the Great War, the memorial, and much of the symbolism ascribed to the site, has functioned as a physical manifestation of the idea of a distinct Flemish ethnicity as opposed to Belgian nationalism. This becomes evident, for instance, in the tower’s physical structure which evokes the tombstones designed for the Flemish soldiers containing the Flemish “AVV-VVK” inscription: “All for Flanders – Flanders for Christ”, which encodes the ideology and symbolism of the Flemish Movement within the language of martyrdom and perseverance (Picture 1).

The wholesale destruction of the first IJzertoren in 1946 served to confirm perceptions of unjust persecution from the Belgian state. As a result, the chapel on the ground floor of the second IJzertoren (rebuilt in 1965) returns the visitor to a resurrected Flemish nationalism that was heightened during the Great War. Two disparate sets of stained glass windows dominate the space.

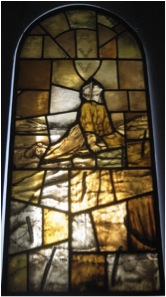

The first set of windows emulates the Stations of the Cross, but the figure of Christ, typically represented moving toward his destiny as the first martyr, is replaced by the WWI soldier crawling in the mud of the front, guided by the AVV-VVK, towards his own submission to the Flemish Movement (Picture 2). The soldier/martyr is reminded of his suffering (Picture 3) and his cause (Picture 4). The windows are executed in the colours of the war front, as shades of brown and a dull golden light echo the ubiquitous mud of the trenches.

The dull, drab colours of the “martyr” windows are in direct contrast to a second set of windows, which are composed in the bright colours of traditional medieval stained glass. This second set of windows begins with an image of two “martyred” Flemish Earls who died resisting the 16th century Spanish occupation.[1] The second window in the series (Picture 5) presents the WWI soldier as a medieval warrior. With the Lion of Flanders emblazoned on the flag behind him, the image conflates the medieval and romantic aspirations of a sovereign Flanders with the experience of the Flemish soldiers in the First World War. A more cultured and educated Flanders rises as revealed by a small figure in the lower right reading Flemish (not French) texts. This image may also refer to the construction of the WWI trenches (note the sandbags) and the reading of 19th century Flemish literature by the members of the Front Movement, a covert political movement organised in 1915 by a group of Flemish soldiers and dedicated to the recognition of Flemish culture and the primacy of the Flemish language.

A second example depicts the triumphant reconstruction/resurrection of the IJzertoren after its destruction in WWII (Picture 6). With the IJzer cross behind him, a Flemish soldier holds aloft a medieval shield with the Lion of Flanders, a symbol of the Flemish Movement. Small crosses and rubble from the first IJzertoren suggest the deaths that make his triumph possible. A woman holds her baby up as an offering toward the Flemish ideal. A third window (not pictured) suggests the solace and vindication the Flemish soldier finds in the figure of the Virgin as she holds a Flemish tombstone adjacent to the scales of justice, serving to underscore the inequality felt by the Flemish soldiers at the hands of the French-speaking officer.

The stained glass windows in the IJzertoren Memorial continue to underscore the tower’s medieval foundations in the struggle for a Flemish consciousness. King Albert, in an attempt to boost army enlistments and national moral, appealed directly to the patriotic pride of the men of Flanders and explicitly recalled the 14th century Battle of the Golden Spurs (1302), a definitive landmark in the development of Flemish political independence. As verified by the stained glass in the IJzertoren, an emphasis on the Lion of Flanders, the symbol for Robrecht van Bethune, the heroic leader of this battle, continued in the post-war years, and has continued to shape Flemish political rhetoric today. Albert promised Flanders ‘equality in right and fact’… after the war. As the promise was not kept, the glass serves as a reminder of the Flemish struggle linking the injustices of the past to the goals in the present.

Karen Shelby is an Assistant Professor of Art History for the Department of Fine and Performing Arts, Baruch College, The City University of New York.

All pictures taken by J. Pingree, 2007.

[1] Graaf van Egmont and Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorne.

Pingback: Carol McFadden is a Icelandic writer | Alexander Mcfadden