Editor’s note: As part of its special issue on Africa, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 11(1) dedicates its features section to exploring the socio-political and historical role of Africa in the International Criminal Court (ICC). The following is an introduction to that section and also appears in Issue 11(1).

Since its establishment, the ICC has concentrated its investigations and operations on the region, applying international law to prosecute large-scale crimes often committed in the context of ethnic conflicts and processes of nation-building. However, recent critiques from a variety of sources, including the African Union, have charged the ICC with jeopardising peace, prolonging ethnic conflict and threatening the national sovereignty of African states. These issues have sparked a number of public and academic debates centring around the role of the Court and the effects of its operation in Africa.

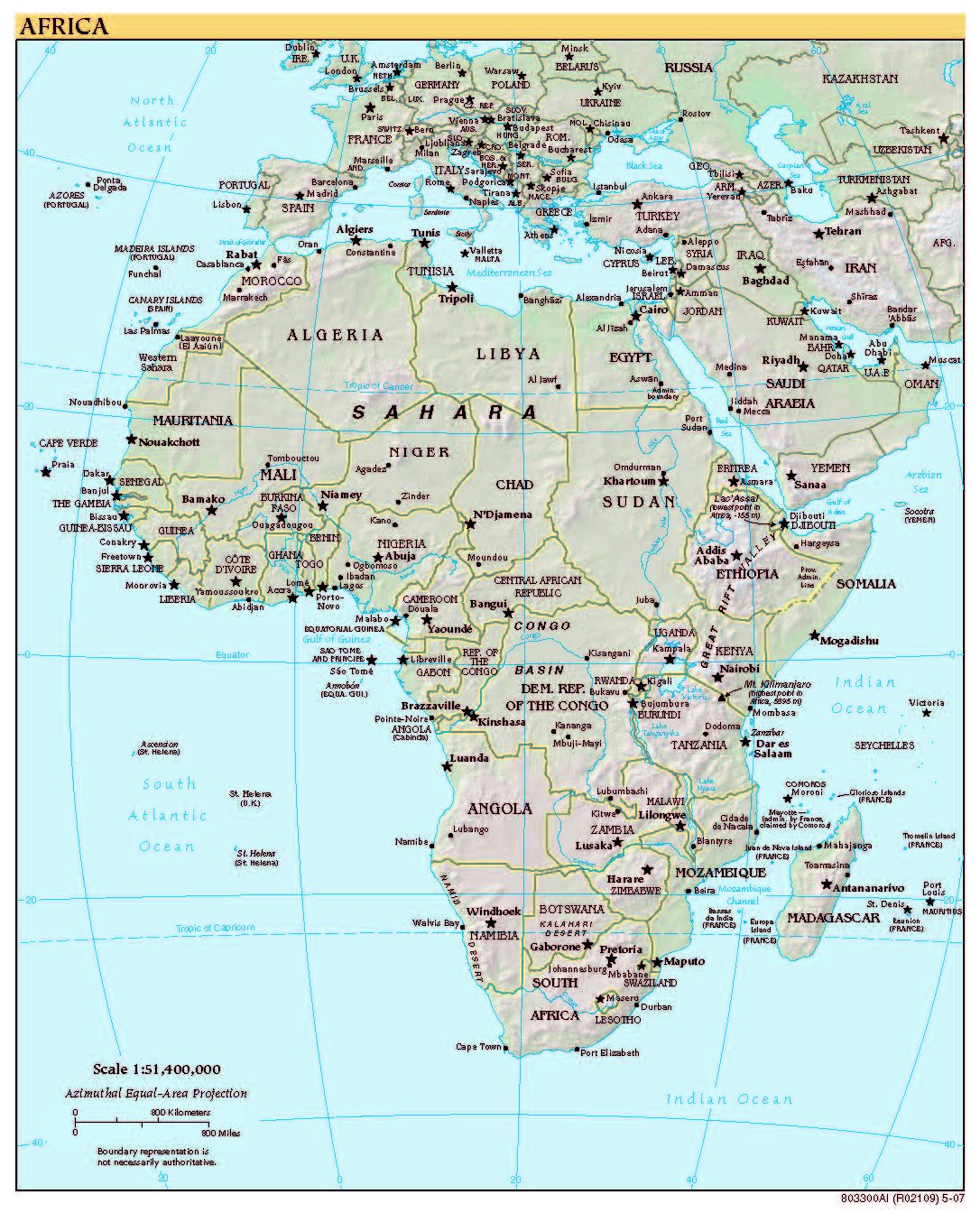

Building upon current discussions, SEN turns the question around by asking whether and to what extent the African context affects the aims and operations of the ICC. Given the fact that Africa constitutes the Court’s main geo-political area of focus, the ICC’s history and development are inextricably linked to the continent. What, therefore, can the Court learn from its history and operation in the African context? Instead of treating Africa as a homogenous geographical category and reducing it to a context of ethnicity-related crimes, we have invited contributions that present the diversity and complexity of issues that have arisen through the involvement of the Court in African countries.

In a piece based on an extract from his forthcoming book, anthropologist Richard Wilson focuses on the Lubanga Trial in arguing that, in this particular case, the Court’s quest for objective documentation and its eagerness to avoid the clichéd rhetoric of ethnicity led the judges to dismiss first-hand experience of the African context provided by the prosecutor’s expert witness in favour of a more ‘scientific’ approach to legal evidence. A particular case sets the framework, therefore, within which the Court develops and utilises its particular criteria about legal documentation.

Kasaija Phillip Apuuli, Lecturer of International Law at Makerere University in Kampala, explains how particular agents in African contexts, who have not been adequately acknowledged in the literature, may critique the ICC’s presence and impede its smooth operations. In his case study from Northern Uganda, some elements from Ugandan civil society have favoured dialogue and reconciliation over the Court’s pursuit of retributive justice. Apuuli describes the tensions between these two antithetical stances and examines the reasons why, in this particular context, both the efforts of the Court and of civil society groups remain static.

The subsequent two articles take an expansionist approach, arguing that the Court needs to extend its role in order to address issues that emerge out of its operation in Africa. Jeremy Sarkin, attorney and professor of Law, who currently serves as Chairperson-Rapporteur for the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, suggests that the Court should move beyond prosecutions and take up a stronger role in restorative justice. In co-operation with national and regional institutions, as well as with civil society, it should work to promote the understanding of human rights. The Court could then potentially address crimes, such as enforced disappearances. Although they are a recurrent pattern of human rights violations in Africa, the Court rarely deals with such cases.

Mehmet Ratip, who is based at the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at the Middle East Technical University, takes the argument further by focusing on violations of environmental and economic rights that, as he argues, are often the root causes of massive crimes that fall under the jurisdiction of the Court. According to Ratip, the ICC should expand its agenda in order to acknowledge and investigate violations of basic rights, such as the right to food, as a means to further its legitimate authority in Africa.

Some of the main themes that are raised in the multi-authored piece are also discussed in the features interview for this special issue. Fatou Bensouda, Deputy Prosecutor of the ICC, answers SEN’s questions on the operations of the Court inAfrica and on recent critiques of its role in the region. The Deputy Prosecutor asserts that African states currently hold a leading role in promoting international criminal justice and they reaffirmed their commitment to the Rome Statute in the first ICC Review Conference, which took place in Kampala in summer 2010.

This Features Section endeavours to re-examine but also interrogate the categories of ethnicity and nationalism that have very often dominated discussions on the role of the ICC in Africa. The invited papers, which argue from diverse empirical and disciplinary perspectives, offer a unique insight into the multiplicity and variety of issues and contexts that have to be taken into consideration in any analysis of the relationship between Africa and the ICC. This is, at least, for any analysis that moves beyond representing human rights violations and discourses in Africa solely through the narrow lens of ethnic conflict and nation-building.

Editor’s note: Readers can gain full access to the articles referenced above in SEN 11(1), which is available for download here.

Test

Test