In his new book, Still Not Easy Being British: Struggles for a Multicultural Citizenship (Trentham, 2010), Professor Tariq Modood sets forth a concept of multiculturalism based on liberal citizenship, moderate secularism and an inclusive idea of what it is to be British.

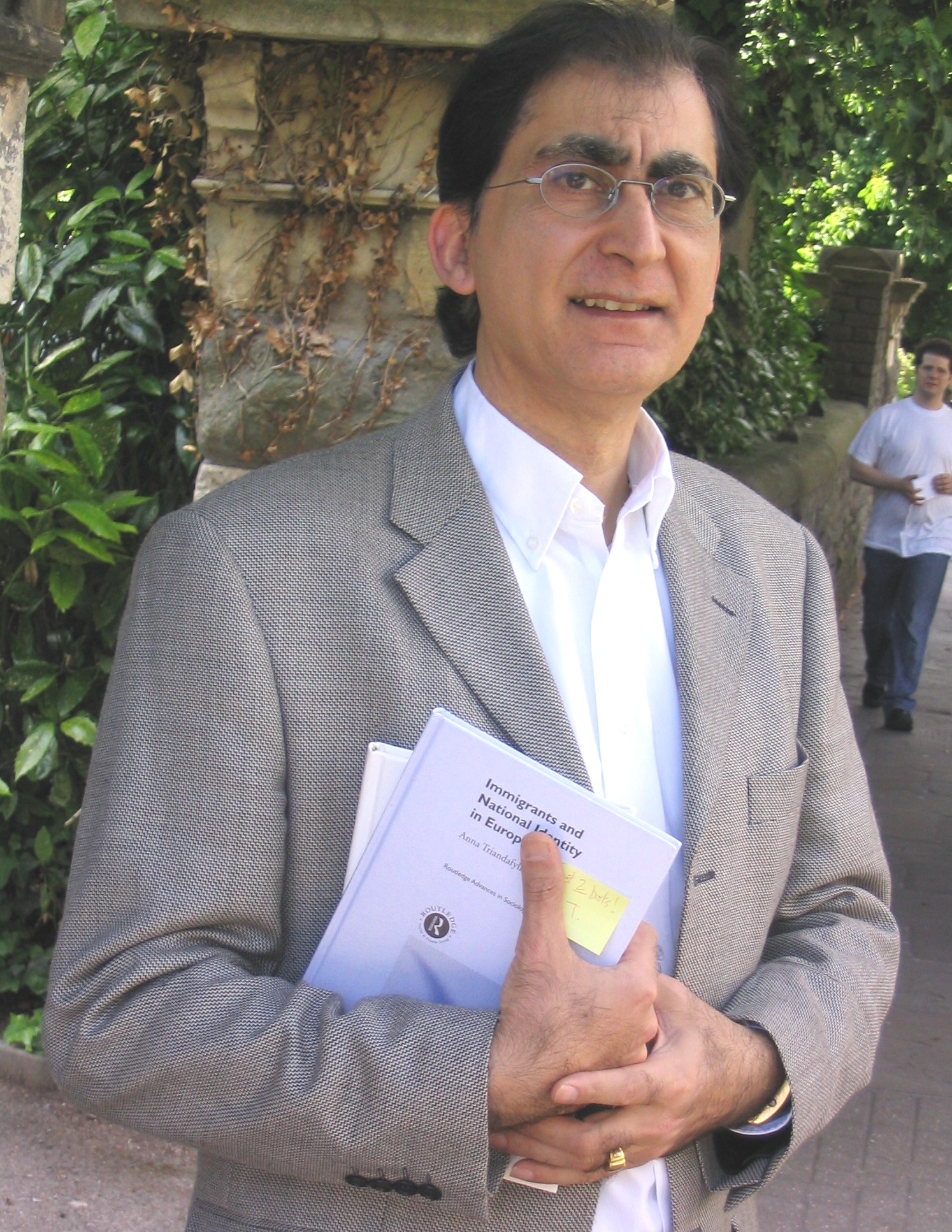

Professor Modood, left, is director of the University of Bristol’s Centre for the Study of Ethnicity and Citizenship and a renowned commentator on Muslim politics. He recently answered questions from SEN’s web editors.

Professor Modood, left, is director of the University of Bristol’s Centre for the Study of Ethnicity and Citizenship and a renowned commentator on Muslim politics. He recently answered questions from SEN’s web editors.

What inspired you to write this book?

The book is a collection of essays and is a sequel to a collection I published in 1992. That was entitled Not Easy Being British and this one is called Still Not Easy Being British. The first collection of essays was mainly a response to developments and controversies around race and ethnicity at the time, especially to the Satanic Verses affair. The sequel has a very similar character. It includes one piece on the Rushdie affair from that time as that piece was not included in the original collection, and re-reading it recently 20 years after it was written, I was amazed at how it had not dated and I still agree with almost every word of it. The rest of the pieces were written much more recently and most of them directly or indirectly are responses to controversies such as the Danish cartoon affair, the storm that followed Archbishop Rowan Williams’ lecture in which he talked about UK law accommodating aspects of Shar’ia law and the ‘multiculturalism is dead’ discourse, especially the arguments that blames multiculturalism for terrorism. All these essays approach these topics from the point of view of what it means to be British today and how these debates are indications of, and struggles in, the evolution of a multicultural Britishness.

How long did this book take to research and write? What were your main challenges?

One essay was written in 1989, all the others were written during 2006 and 2010. Some are short pieces written in a couple of days while a controversy was still raging; others are products of several years of reflection and maturation.

What kind of field research did you conduct?

Only one of them is directly based on field research. After the attack in the USA on 9/11 I wanted to show that the ways of thinking of most politically active Muslim intellectuals and community activists in Britain were not based on a ‘clash of civilisation’ perspective but were either directly informed by or were consistent with the currents of political multiculturalism in Britain. I sought to demonstrate that their ideas owed more to contemporary liberal egalitarian debates rather than Islamic or Islamist textual sources. Or, to put it another way, that their intellectual and political framework reflected a ‘moderate Muslim’ perspective rather than a radical Islamism. I managed to get a small grant from The Gulbenkian Calouste Trust and was able to employ Fauzia Ahmad to work with me on the project. We designed an interview brief and other research tools and Fauzia did nearly all of the interviews – about 20 individuals in London. I was very lucky to have Fauzia as she understood the issues, knew many of the individuals (as did I), and is a very good listener. The interviews were fairly complex with a lot of references to ideas and debates and so they could not really have been done by someone unfamiliar with these debates. The biggest challenge in the analysis was to come up with a typology to classify the different kinds of Muslims and their views. Another major challenge was to find a meaning for the term ’moderate Muslim’ when most of the respondents had said they did not use or like the term. To find out how we did this, you will have to read the piece – and you can also see whether the analysis is robust enough to withstand the complaint of Baroness Warsi, the Conservative Party Vice-Chair, against the use of the idea of moderate Muslims.

What do you hope students and researchers will get out of this book?

I would like people to see the zig-zagged character the debate has taken and that while levels of violence in the form of terrorism were unforeseen and are shocking and have generated real fear on all sides, we have been and continue to move towards, however imperfectly, a form of multicultural Britishness which belies the ‘multiculturalism is dead’ rhetoric. I think a certain hopefulness has been lost and we have rightly and belatedly emphasised what we have in common as Britons, but a politics which reconciles equality across difference is still alive and important in shaping majority-minority relations.

What advice do you wish someone had given you when you began this project?

Well, as you will have gathered, the book is not based on a single project but is a collection of essays around a single theme. Two pieces of advice that colleagues often give me is firstly to not see things too much in terms of difference but to see the commonalities. But they then go on to emphasise class, gender, age and so on – namely characteristics that differentiate people. So, I take the lesson to be to not reduce people and situations to one category. I like to think that I do not make this reduction just as others who prioritise class or gender equally think that they avoid reduction to those concepts.

The second advice I receive is not to be too normative. I think all social science in one way or another is driven and framed with certain normative ideas, such as non-discrimination or equality or peaceful co-existence. I prefer to bring these normative concerns into the foreground rather than leave them in the background. I believe that is necessary for the kind of public intellectual engagement I aspire to achieve.

What are you working on right now?

I am writing a book which develops the ideas of the last chapter of Still Not Easy – that is to say, to recognise that the character of the political secularism of most of Western Europe has not been, is not and should not be about requiring the evacuation of organised religion from politics or even the state. If I can make this argument I hope to reduce the scale of opposition against the full accommodation of those Muslims who prioritise their religious identity. Political secularism is essential to multicultural citizenship but does not require religious citizens to keep their religion and politics separate. If this sounds contradictory please look at the last essay in my book.

When working on a book, how do you begin your writing day?

I am afraid I usually have too much going on – research projects, unfinished contributions to edited books, co-editing new books, co-editing the journal Ethnicities, organising and giving papers at conferences, public engagement, not to mention PhD students and teaching – to be able to devote a whole day to a book. I try to do some reading and noting on some mornings, and writing on some evenings and on Sunday; the rest of each week and sometimes even the whole week is taken up by some of the other activities I have listed. My wife complains I am too addicted to answering unnecessary emails and am too easily distracted – like answering your questions when I should be thinking why my current chapter is not falling into place!

In what conditions do you do your best writing?

I live on a hill and our house has a very large bay window which has lovely views and gets the sun all day. That’s a great place to work or at least to feel good about life. On a blue-sky day, even when there is snow outside, the window so magnifies the sunlight that it is a very happy room. I have a desk in the middle of the bay and a sofa in the room and currently they are my best place to work.

Which writers – of any genre – do you most admire?

I enjoy the simple elegance and gentle wit of Jane Austen’s prose; the intellectual sharpness of Plato’s Socrates; and the stylishness of Michael Oakeshott’s essays.

If you had not gone into academic research, in what field would you have liked to work? Why?

I like the cut and thrust of intellectual life as well the logic of inquiry and the uncovering of what was obscure. Perhaps one can find these in a court of law, or in investigative journalism – perhaps in running a current affairs TV or radio programme. I think however I prefer the mid-distance horizons and timelines of academia than the pace at which most of the world has to reach conclusions.

Editor’s note: To find a link to Professor Modood’s recent response to Prime Minister David Cameron’s speech on multiculturalism in Britain, as well as the transcript to Cameron’s talk, click here.

Pingback: New SEN blog « Nationalism Studies