Introduction

In February of this year we witnessed the beginning of the 2014 Crimean Crisis. For decades this region, home to an ethnically Russian majority, as well as eastern Ukraine more widely, has been oriented more towards Russia than (western) Ukraine. Political instability in Ukraine centred in Kiev and a decision by the President Viktor Yanukovych to reverse moves for closer ties with the European Union in favour of deepening those with Russia, led to Yanukovych fleeing the capital after an outbreak of violence between security forces and protesters there. This was followed by disturbances in the Crimean region, during which armed pro-Russian and Russian state forces began to take over the region. Following this, the Crimean Parliament called for a referendum on the region’s constitutional status. Subsequently, based on the referendum’s outcome, the Crimean Parliament decided on secession from Ukraine in order to join the Russian Federation. Moscow agreed, and on March 18th the Russian government and the separatist Crimean government signed a treaty to that effect. The annexation – the first of its kind anywhere in Europe since 1945 – was internationally condemned as illegal and illegitimate, and the region remains in dispute. Since then, an armed conflict has been in occurrence between Ukrainian troops and separatist militias, as well as with Russian forces inside Ukraine. Spreading out from Crimea, a general conflict has arisen in eastern Ukraine between the Ukrainian state and other breakaway ‘republics’ (including in the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblast areas, both part of the larger Donbass region) that have oriented themselves towards Russia. In August, in a conference in Yalta (where, perhaps significantly the map of post-war Europe was decided by the Allied powers during the Second World War between Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin), Russian President Vladimir Putin affirmed that under no circumstances would the annexation of Crimea be reversed. Unrecognized elections that have just taken place in Donetsk and Luhansk (where there are now around 15,000 Russian troops) may, as argued by Ukraine scholar Taras Kuzio, establish ‘a de facto new border with Ukraine.’

Seventy years ago, in his seminal study The Idea of Nationalism: A Study of its Origins and Background (1944), the historian Hans Kohn distinguished between ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ forms of nationalism. Since then, despite its shortcomings, this distinction, and its re-workings in forms such as the ‘civic’-‘ethnic’ dichotomy remains highly influential in its different forms, being a kind of ‘theoretical common sense’ in nationalism studies.

For Kohn, while ‘Western’ forms of nationalism were based fundamentally on ideas of citizenship as opposed to ethnic belonging, ‘Eastern’ forms of nationalism were based on a collectivist and illiberal conception of ethnic descent and commonality. Again, this seems to match with the nature of the Crimean conflict: ethnic Russians have rejected established state boundaries in favour of far more ‘meaningful’ commonalities with the Russian Federation based on common culture and historical memories.

While Kohn did not believe that his distinction matched exactly with European geography, it has not been uncommon for central and eastern Europe, for most of its history a region contested by rival empires, to be seen as a borderland in which different forms of nationalism have come into conflict, often violent.

In the Crimean conflict we can see, arguably, Kohn’s conflict played out in literal terms, in an antagonism between ‘west’ and ‘east’ in Ukraine. This is, after all, a ‘common sense’ interpretation of the conflict, insofar as it matches the ‘common sense’ distinction of civic and ethnic nationalisms among many scholars of nationalism (as noted by Rogers Brubaker in his essay on civic and ethnic nationalism in his 2004 book Ethnicity Without Groups).

Yet how useful are these ‘common sense’ notions to understanding the conflict? Does the political and media narrative hold weight in terms of what scholars have come to understand about nationalist fissures in Ukraine, a ‘graveyard’ of three empires?

With more than half a year having passed since the beginning of the conflict that remains ongoing, and has now claimed over 4,000 lives since April, and may yet escalate further with the order for the deployment of more Ukrainian troops to the disputed eastern regions, SEN Online will provide a brief and accessible survey of some recent important English-language scholarship on the history of nationalism in Ukraine and the Ukrainian-Russian borderland, and seek to examine its relevance for how contemporary affairs in Ukraine may be analysed and understood. This will complement a more extensive analysis of the conflict in Ukraine that will appear in a special issue of Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism next year (15.1, April 2015).

The theoretical study of nationalism came relatively late to the analysis of the nations of the Soviet Union, with sustained archival research unencumbered by political constraints by both Soviet and international scholars not really being possible until the post-1991 period. As such, events such as those that have taken place in the Ukraine in the past several months, less than twenty-five years since the end of the Soviet Union, provide an opportune moment to reflect on how recent historical scholarship on nationalism has come to understand the problem of nationalism in one of the classic ‘graveyards’ of empire and post-imperial ‘borderlands’.

The first part of the survey will consider how historians have observed the west-east divide in Ukrainian history, and its significance for Ukraine and nationalisms in the country.

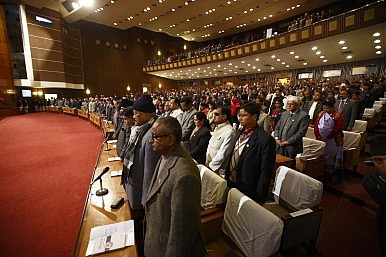

NB: Images sourced from Reuters

References

‘Ukraine Crisis: Russia vows troops will stay’, BBC News, 2/3/14

‘Ukraine Crisis: Russia isolated in UN vote’, BBC News, 15/3/14

‘Crimean Parliament formally applies to join Russia’, BBC News, 17/3/14

‘Crimea Crisis’ Russian President Putin’s speech annotated’, BBC News, 19/3/14

‘Putin to decide next moves in standoff with West over Ukraine’, Eurasia Daily Monitor, 11, 150, 14/8/14

Russia annexes Donbass but loses Ukraine’, Financial Times, 4/11/14

‘Ukraine crisis: Poroshenko orders troops to key cities’, BBC News, 4/11/14

‘Ukraine Crisis: What It Means for the West by Andrew Wilson – review’, The Guardian, 5/11/14

Books

Rogers Brubaker, Ethncity Without Groups (London, Harvard University Press, 2004)

Hans Kohn, The Idea of Nationalism: A Study of its Origins and Background (New York, Macmillan, 1945)